Skopje – The

World´s Bastard

Skopje – The World´s Bastard

Skopje

2009 – 2011

—

Forschungsprojekt

Projektpartner

Milan Mijalkovic

Julian Mullan (Fotos)

Publikation

Mijalkovic, Milan/Urbanek, Katharina: Skopje – The World´s Bastard. Architecture of the Divided City. Wieser Verlag, Klagenfurt 2011.

(mazedonische und albanische Ausgaben: Goten Publishing, Skopje 2011)

Ausstellung

Skopje – The World´s Bastard, Museum of the City of Skopje, 10.05. – 30.05.2011

Vortrag

Vortrag und Diskussion „Skopje. The World´s Bastard“, Buchmesse Leipzig, 18.03.2011

Vortrag und Buchpräsentation „Скопје – Светското Копиле“, Museum of the City of Skopje, 10.05.2011

Förderung

gefördert durch das BKA Österreich

Links

Milan Mijalkovic

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso (Interview)

Balkan Insight (Rezension)

Wieser Verlag

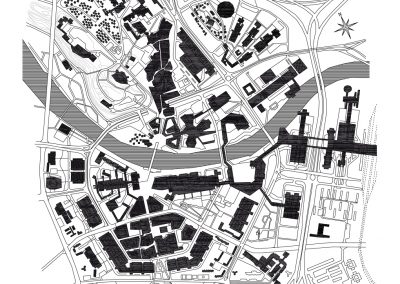

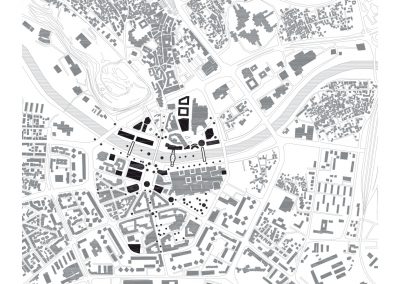

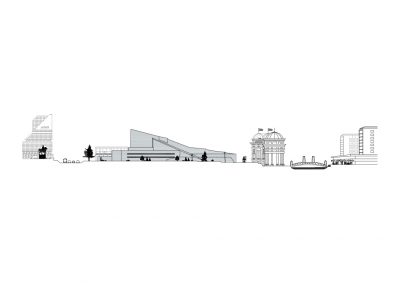

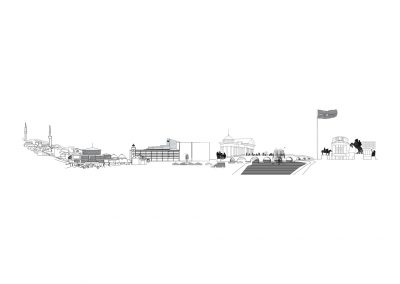

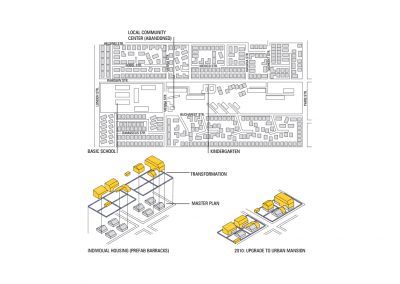

Skopje, the capital of Macedonia which had been declared an “Open City” in the 1960s, has been transforming into a prototypical “Divided City” in recent years. After the armed conflict between members of the Albanian minority and the Macedonian army had almost turned into a civil war in 2001, the gap could not be bridged anymore. Since the dissolution of Yugoslavia the two ethnic groups had been veering away from each other and defining their own inseparable identity. Religious symbols demonstrate territorial claim: minarets sprout in Albanian neighbourhoods, whereas on the hills of Christian-Macedonian areas crosses rise up to the sky. Skopje – The World’s Bastard explores the city’s urban development with regard to its character of a Divided City. It traces material and virtual spaces of conflict and negotiation from the utopias of the 1960s through the frustrations of the 1990s to the actual constructions of identity and places them into a global context.

weiterlesen...

The title of the book “Skopje – the World´s Bastard” suggests to consciously turn our attention towards the city´s heterogeneous and multi-layered character, to accept and even value its complex bonds with the international world. The term “bastard” signifies an anomaly. It is a hybrid, the product of two disparate parents that no one has actually wished for. It speaks of a tumultuous origin, followed by neglect, disregard, and denial. But at the same time it speaks of strength and independence, of tactics to learn from the differences, to use the in-between spaces and to be free to move.

Throughout its history the city of Skopje has experienced numerous times of invasion, occupation, and destruction – constantly followed by rebuilding and the attempts either to reconstruct the idea of the city or to redefine Skopje as something new – depending on who had won the last battle. Layers of meanings and identities overlap in this city and often they oppose each other.

For centuries the opposing pair of the (Christian) “Occident” and the (Muslim) “Orient” played the role of the disparate couple. It found its successors in the “East” and the “West”. Indeed, this parentage signifies not only Skopje or Macedonia, but the Balkans as a whole. Neglected and riddled with stereotypes, the region has been perceived by the West as an incomplete or anomalous self rather than the opposing other. In being largely Orthodox, and thus still a variety of Christian, but not Muslim or – focusing on Yugoslavia – being Communist but not under Russian domination, the Balkans and their defects have been tied to Europe. Like in other Balkan cities this (self-) perception as anomalous or incomplete has been influencing Skopje´s development, especially from the beginning of the 20th century. Urban planning and its key architectural projects have been driven by the deep wish to “become whole”. But different from any other city of the region, the fate of being an offspring of disparate parents culminated strikingly in Skopje´s rebirth that followed the earthquake of 1963. The result is a unique character, an impure Bastard with its inseparable and unfulfillable desire to get whole.

Today in 2010, this desire seems to be stronger than ever before. Current urban planning is ruled by an idea of offensive identity building that is based on a whole range of Western myths of modernity: from origins in the times of Alexander the Great through the opposition to the Ottomans to the absolute belief in commercialization. Paradoxically, the recurrent attempts to gain a distinct identity and to finally Europeanize indeed bear in themselves the danger of expediting the division of the city rather than its completion. The wish to become whole leads to the city´s interior break-up.

Today Skopje is willing to deliberately abandon a great deal of the Bastard´s ancestry and therefore its potential. But it is in the Bastard´s nature that neglect and denial let it develop refined tactics to survive and reappear on the ever so slick surface